Most engineers design systems to work.

Very few design systems to survive.

There’s a massive difference.

If failure is “acceptable,” you optimize for:

- Speed of delivery

- Cost

- Simplicity

But if failure is not allowed — financial systems, healthcare platforms, emergency services, aviation, large-scale infrastructure — your mindset changes completely.

You stop designing software.

You start designing resilience under chaos.

This is how I would design a system where failure is not an option.

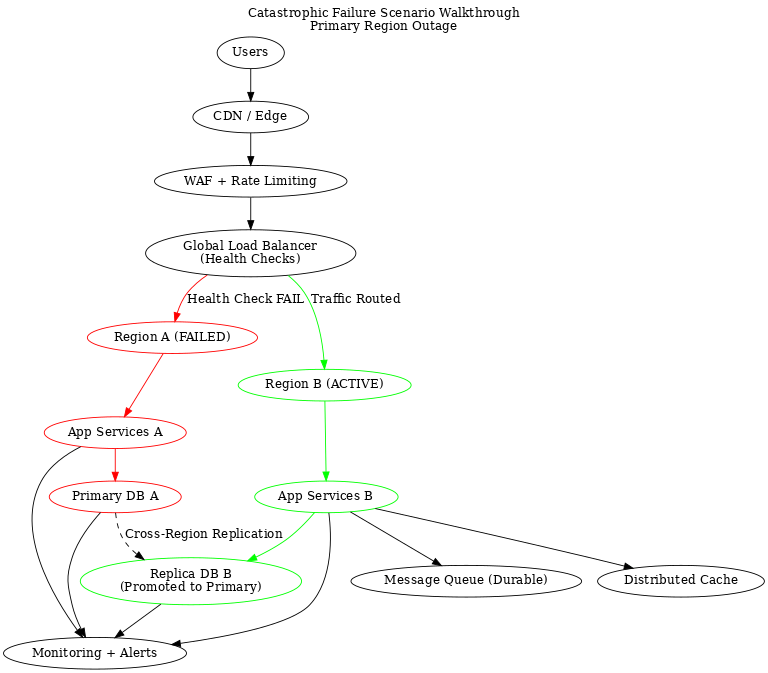

Diagram: Catastrophic failure scenario walk-through: Primary region outage

🚨 First Truth: “No Failure” Does NOT Mean “No Outage”

This is where junior thinking collapses.

Failure is inevitable.

What’s unacceptable is uncontrolled failure.

So the real goal becomes:

The system must fail safely, predictably, and recover automatically.

That’s the philosophy behind everything that follows.

🧠 Step 1 — I Design for Failure Before I Design Features

Most teams start with:

“What should the system do?”

I start with:

“How will this system break?”

I list failure categories first:

| Failure Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Infrastructure failure | Server dies, AZ goes down |

| Network failure | Packet loss, latency spikes |

| Dependency failure | Third-party API timeout |

| Data failure | Corruption, replication lag |

| Human failure | Bad deployment, bad config |

| Traffic failure | Sudden 10× load spike |

| Security failure | DDoS, malicious traffic |

If your architecture doesn’t answer these, it’s not production-grade — it’s a demo.

🧱 Step 2 — Architecture Pattern: Redundancy Everywhere

If a component exists only once, it is a liability.

Core Design Principle:

Every critical component must have a backup that can take over without humans.

Infrastructure Layer

- Multi–Availability Zone deployment (minimum)

- Multi-region for critical workloads

- Stateless services behind load balancers

- Auto-scaling groups, not fixed servers

If one region dies, traffic shifts automatically. No war room.

🗄 Step 3 — Data Is the Real Single Point of Failure

Most architectures look resilient… until the database fails.

That’s when reality hits.

My Data Strategy

✅ Replication

- Multi-AZ replication

- Cross-region replication

- Read replicas for load distribution

✅ Backups

- Automated snapshots

- Point-in-time recovery

- Immutable backup storage

✅ Data Corruption Protection

- Write-ahead logging

- Versioned storage

- Soft deletes for critical entities

Because in high-stakes systems:

Losing data is worse than downtime.

🔌 Step 4 — I Assume Every Dependency Will Fail

This is where most production outages come from.

Defensive Design Patterns

| Pattern | Why |

|---|---|

| Timeouts everywhere | No request waits forever |

| Retries with backoff | Handle transient failures |

| Circuit breakers | Prevent cascading collapse |

| Bulkheads | Isolate failures to one subsystem |

| Graceful degradation | Partial functionality > total outage |

If your system crashes because a non-critical service is slow, your design is fragile.

🌊 Step 5 — Traffic Surges Should Be Boring

A system where failure isn’t allowed must treat spikes as normal.

How:

- Auto-scaling based on CPU + queue depth

- Rate limiting at the edge

- Caching at multiple layers (CDN, app cache, DB cache)

- Async processing for non-critical flows

If your system collapses under growth, your architecture was lying to you.

🧍 Step 6 — Design Against Human Mistakes

Most outages are not caused by hardware.

They’re caused by people.

So I reduce the blast radius of humans.

How I Do It:

- Blue/Green deployments

- Canary releases

- Feature flags for risky features

- Automated rollbacks

- Infrastructure as Code (no manual server changes)

If a developer can break production with one command, your process is broken.

🧪 Step 7 — Observability Is Not Optional

You cannot prevent failure if you can’t see it forming.

Mandatory Stack:

- Centralized logging

- Metrics (CPU, memory, latency, error rates)

- Distributed tracing

- Real-time alerting

- Synthetic monitoring

If users discover the outage before your monitoring does, your system is blind.

🧯 Step 8 — Failure Containment Over Failure Prevention

You cannot stop all failures.

But you can contain them.

Example:

Bad design:

One service crashes → whole platform down

Resilient design:

One service crashes → that feature disabled → rest of platform works

That’s maturity.

🧩 Step 9 — Simplicity Becomes a Reliability Strategy

Complex systems fail in complex ways.

If failure is unacceptable:

- Avoid unnecessary microservices

- Prefer modular monoliths when scale doesn’t demand distribution

- Fewer moving parts = fewer failure paths

Over-engineering is a hidden reliability risk.

🧑💼 Step 10 — Leadership Matters More Than Technology

Here’s the part tutorials don’t talk about.

Highly reliable systems come from:

- Blameless postmortems

- Incident response training

- Clear on-call ownership

- Runbooks for emergencies

- Culture of reporting near-misses

Reliability is not an architecture diagram.

It’s an organizational discipline.

🤖 AI Changes the Game — But Not This Part

AI can help:

- Predict anomalies

- Analyze logs

- Suggest scaling

But AI cannot replace:

- System trade-off decisions

- Risk modeling

- Failure prioritization

This is where senior engineers stay valuable.

🎯 Final Reality Check

Designing systems where failure isn’t allowed means:

- Slower development

- Higher infrastructure cost

- More process

- More testing

But in certain domains, the alternative is:

- Financial loss

- Legal consequences

- Human harm

And suddenly, “move fast and break things” sounds childish.

🧠 The Mindset Shift

Average engineers ask:

“How do we make this work?”

Senior engineers ask:

“How does this behave when everything goes wrong?”

That’s the difference between building software…

and building systems that survive reality.

Leave a comment